Exactly 110 years ago one of the most unsavoury events in horticultural history reached its climax at the Chelsea Flower Show, 1914 – or to be more precise, outside the show.

Ellen Willmott didn’t have anything to do with the actual spat, so how come she found herself at the epicentre of the Unpleasantness at Chelsea and why is she more remembered for it than the characters involved?

The Show had officially begun the year before, in 1913, after a very successful test-run the year before that. Ellen had been there and picked up all the promotional postcards, like this one on the Suttons stand:

The RHS had outgrown their previous showground in Temple Gardens and everything was going rather well. Events had happened at Chelsea before that, but much smaller.

Image (c) Berkeley Family and Spetchley Gardens Trust

Of course Ellen had been heavily involved for years, both as an exhibitor and judge (note the handwritten bit of the pass above…) – by the time the Society had moved to Chelsea she was mainly judging. So she had a lot to lose, face-wise.

What on earth made her risk that reputation by standing at the entrance, with a large leather satchel, handing out scurrilous pamphlets insulting a dear friend?

Image (c) Berkeley Family and Spetchley Gardens Trust

I don’t think this is THE satchel by the way, though I was excited that it might be when it fetched up. When it was finally cleaned it looked more like a travel writing case, but I suspect it would have been something very similar.

Image (c) Berkeley Family and Spetchley Gardens Trust

The whole sorry business had started some years previously with Ellen’s great friend, Sir Frank Crisp. Ebullient, friendly, over the top, a great practical joker and microscope fanatic, as in this 1891 Vanity Fair portrait shows…

…he was unfortunately very thin-skinned when it came to people joking about him…

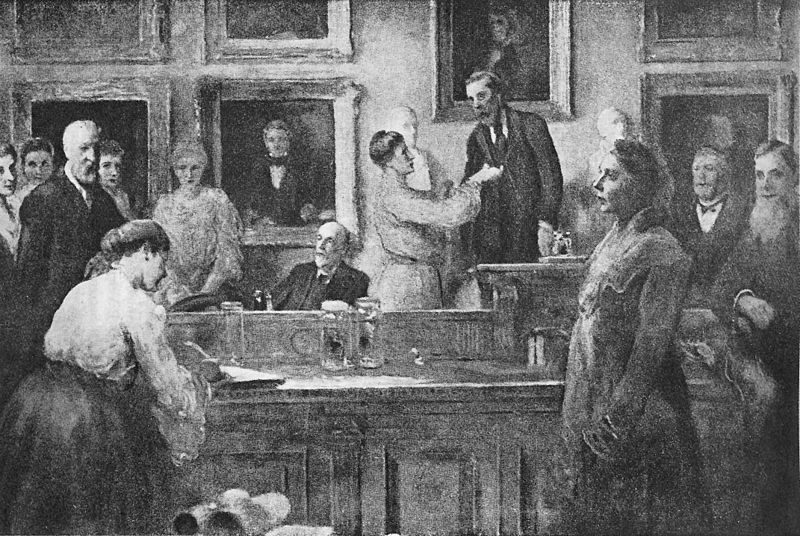

Sir Frank would have first met Ellen at the inauguration of the first women Fellows of the Linnaean Society but I don’t think they were friends at this point because she is not in a painting that he commissioned of the event:

Instead they seem to have met again ‘by accident’ (we don’t know what the occasion was) a few years later and very quickly and intensely become friends.

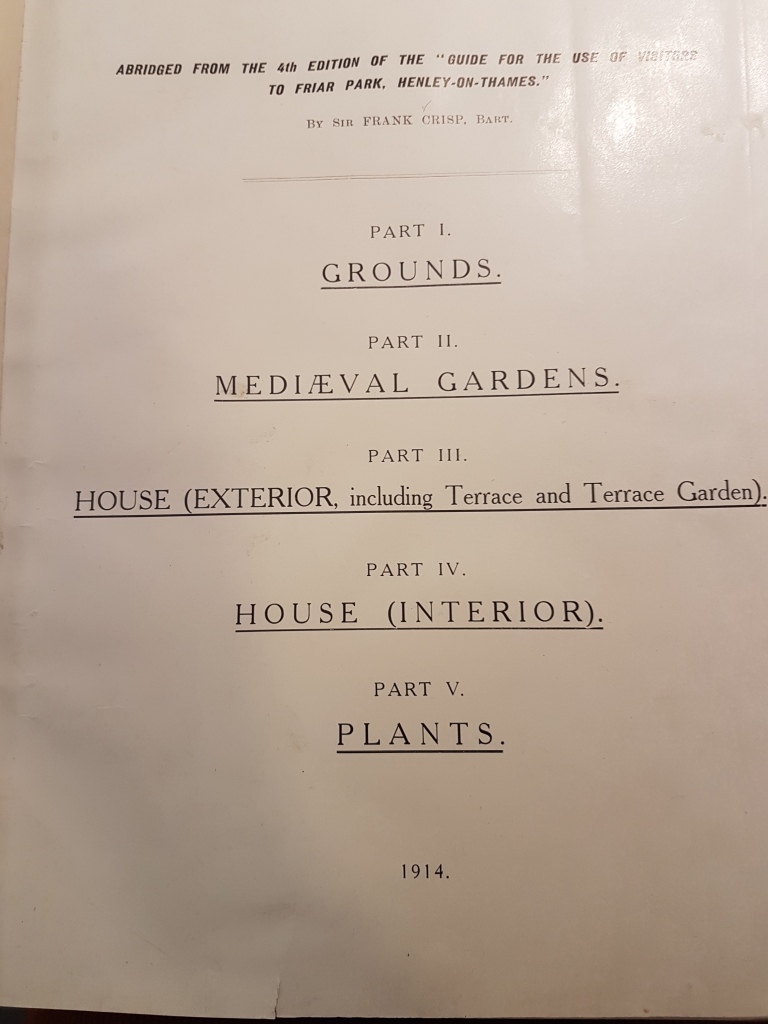

Sir Frank had built a veritable theme park of a garden at his mansion in Henley on Thames.

There are all manner of stories about Friar Park that you can read about on the internet, but I am most interested in its early years and Sir Frank’s nutty garden. It included a massive sculpture park a lake with an underwater grotto you could punt through in a boat, topiary, Japanese and Chinese gardens and any number of caves and visual puns. It was so (intentionally) mad that Sir Frank even had guide books printed for visitors:

Image (c) Berkeley Family and Spetchley Gardens Trust

In 1910 his latest project was a new alpine garden, to be bigger and grander than any before…

On the surface, horticultural bigwigs were a tight bunch, visiting each other’s gardens and making nice noises about them. Beneath the froth, however, things were not always quite so pretty and alpine gardening seemed to bring out the worst in some.

New gardeners arrived on the scene with something to prove and something to say. Some, like horticulture’s brilliant, caustic enfant-terrible Reginald Farrer, said that something extremely well, in a number of best-selling books.

His gloriously bitchy comments about supposedly-inferior rock gardens by – shock – middle-class people were excruciating because they were often painfully accurate.

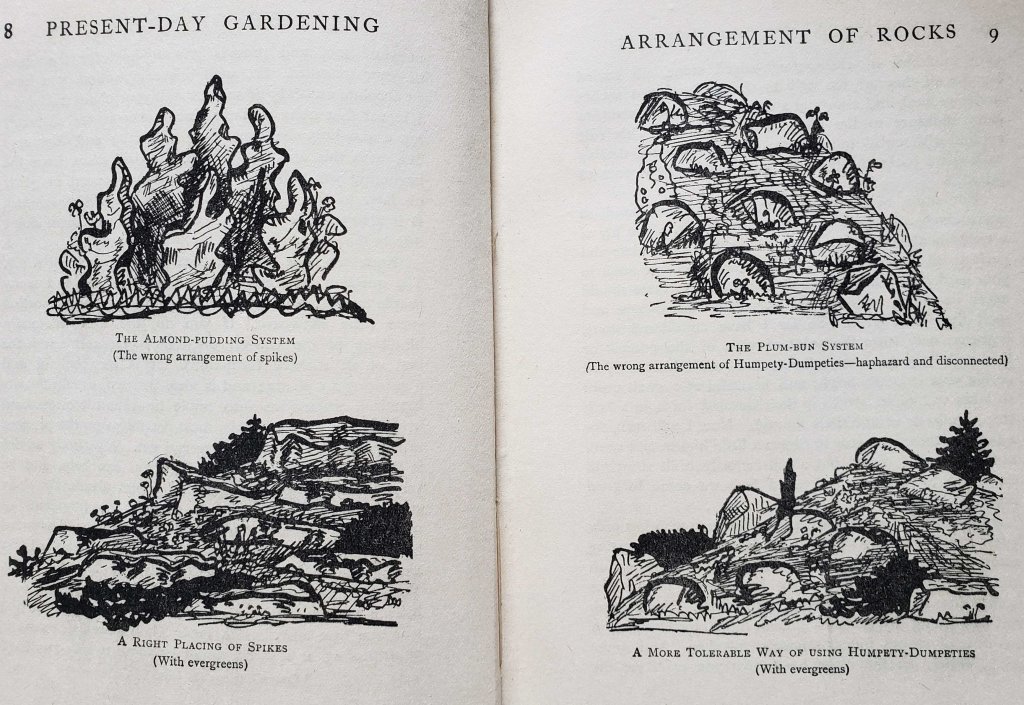

He included extra description for the various heaps of earth dotted with rubble topped with the odd aubretia that he most despised, christening them with names like ‘almond puddings,’ ‘plum buns,’ ‘Devil’s lapfuls’ and even ‘dog’s graves’.

His jibes elicited sniggers from ‘true’ alpine gardeners but he didn’t merely reserve comment for the honest efforts of ‘lower orders’ doing their best. Farrer also lampooned wealthy people who had alpinums created for them at vast expense but, in Farrer’s opinion, with zero taste.

Sir Frank solicited Ellen’s advice on creating his new wonder and commissioned Backhouse of York, who had made Ellen’s garden, to create a new alpine garden for him. The foreman was also recommended by Ellen, Richard Potter, who had overseen all her own rock work.

In many ways Crisp was only doing as Reginald Farrer had suggested:

Have an idea and stick to it. Let your rock–garden set out to be something definite, not a mere agglomeration of stones. Let it be a mountain gorge, if you like, or the stony peak of a hill, or a rocky crest or a peak.

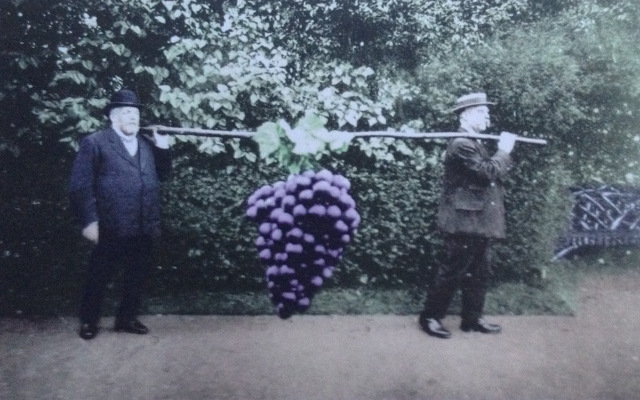

Sir Frank had done exactly that. He built a scale model of the Matterhorn, using coloured gravel ‘scree’, large expanses of massed alpines and even metal chamois mountain goats.

The three-acre Alpine Garden took 7,000 tons of stone and 4,000 plants, and involved waterfalls, pools, mountain paths, bridges, chalets, caverns, precipices and even a glacier with an ‘ice grotto’. It stood between 30 and 40 feet high; crampons would not have been without their uses to visitors.

Sir Frank had had his idea and stuck to it, just as Farrer instructed.

The garden was filled with plants supplied by Ellen Willmott, and she was a very regular visitor.

She enjoyed Friar Park so much that on hearing the devastating news that her sister had cancer in July 1914 (two months after the Unpleasantness at Chelsea), she would bring her nephew and nieces to Sir Frank’s theme park to try to take their mind off the numerous visits Rose was taking to the London Radium Institute for some of the country’s earliest radiotherapy.

Teetering on the very edge of kitsch, Sir Frank’s garden received a mixed reception. Famous alpinist Henri Correvon loved it, as did William Robinson in The Garden. Others found it irreconcilably naff, and while not actually naming Friar Park, it’s obvious who Charles Thonger is referring to in this tirade:

…a new form of desecration in the gardens of the wealthy. I have seen an example of this recently, and can only regret that the owner of that most precious heritage, an old-fashioned English garden, should be so misled as to convert a sunken court into an Alpine peepshow, which might well serve as a sixpenny attraction at Earl’s Court.

Poor Sir Frank’s alpine fantasy was even the subject of an unflattering cartoon in Punch. This is, frankly, unfair. It is clear from the way it is presented – complete with visual gags – that the whole garden has been made firmly tongue-in-cheek (one of the caves featured a fake skeleton – surely no one thought he was being serious…) and the guidebook, which went through several editions and which includes comic images and trick photography…

Image (c) Berkeley Family and Spetchley Gardens Trust

…is nothing short of (deliberately) funny but criticism from some quarters was so very hostile that Sir Frank suddenly became sensitive about the whole thing. He was good-humoured about any criticism of his kitschy settings but drew the line when his choice of plants was attacked by people comparing the masses of alpines to the sneered-at-by-the-cognoscenti Victorian carpet-bedding.

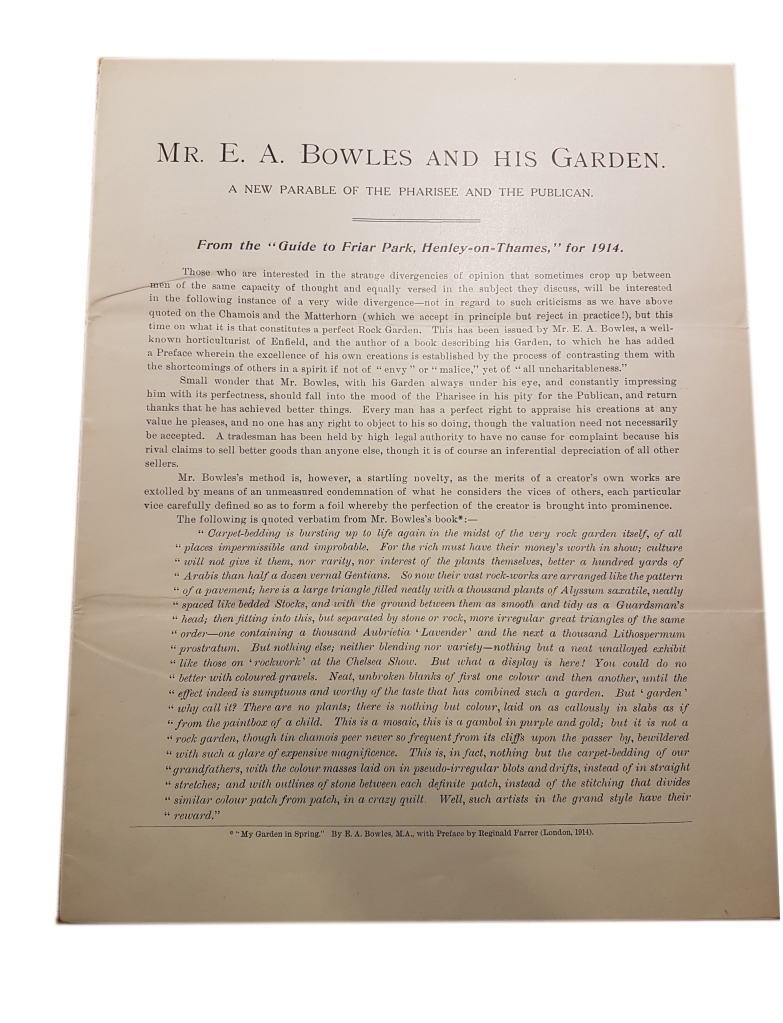

In 1913 Reginald Farrer used the foreword of a new book by the gentle, unassuming Edward Augustus ‘Gussie’ Bowles to tear a strip off this new, vulgar style of rock gardening, twisting the knife by implying the (unnamed) Frank Crisp was not, somehow, a ‘proper’ plantsman and making little effort to conceal who he was talking about.

“You could do better with coloured gravels,” he wrote, continuing

Neat, unbroken blanks of first one colour and then another, until the effect is sumptuous and worthy of the taste that has combined such a garden. But ‘garden’ why call it? There are no plants; there is nothing but colour, laid on as callously in slabs as if from the paint-box of a child. This is a mosaic, this is a gambol in purple and gold; but it is not a rock garden, though tin chamois peer never so frequent from its cliffs upon the passer by.

Sir Frank snapped.

Apoplectic with fury, he persuaded garden titan William Robinson to print a tirade he’d penned himself in The Garden, directing bile not at Reginald Farrer but poor, innocent Gussy Bowles. Not content with this, Sir Frank reprinted Mr Bowles and His Garden: A New Parable of the Pharisee and the Publican in pamphlet form.

Image (c) Berkeley Family and Spetchley Gardens Trust

It is unclear when the feud between Ellen Willmott and Reginald Farrer had begun but by the time of the ‘Crispian Row’ it had definitely been going for ‘some time’.

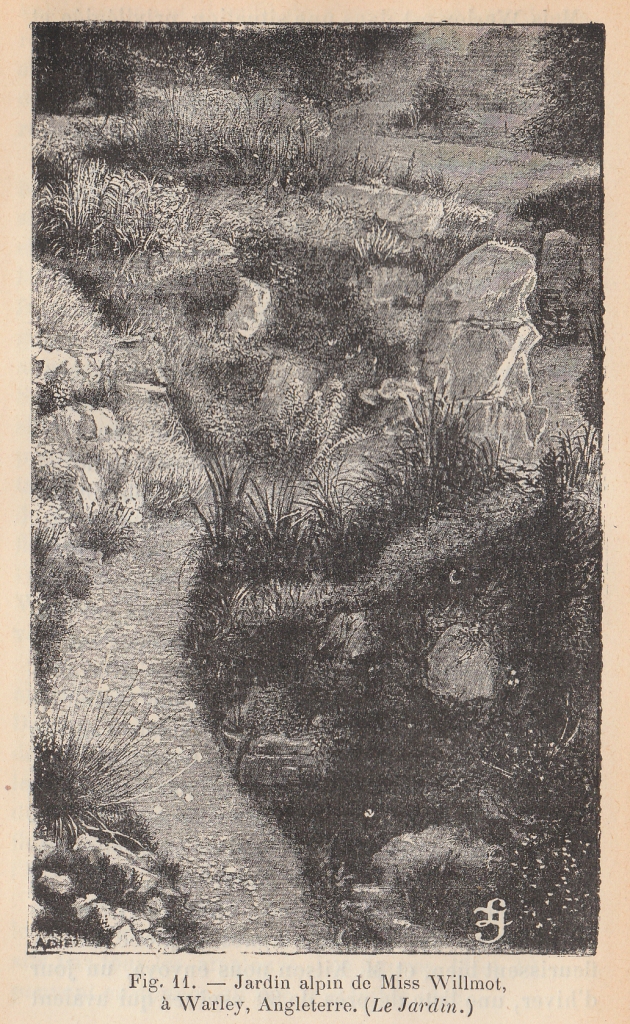

When he had first seen Willmott’s alpine ravine Farrer was (for him) moderately polite: “At Warley, again, there is the Gorge-design to be studied”, though he could not resist a barb in the tail, adding,

“to my own personal taste, a trifle too violent to be altogether pleasant.” *

By 5th March 1910, a double book review in Saturday Review where Farrer’s latest book is compared unfavourably (by a friend of Ellen’s) to Willmott’s Warley Garden in Spring and Summer, is so very partisan that it is clear the animosity was in full flow. Farrer was also jealous of Willmott’s friendship with Bowles, once snapping that Bowles should ‘marry the cankered Ellen at once and have done with it’.

Many people have speculated that this is why Ellen had reacted so badly to Farrer – that she was frustrated in love for Bowles and jealous of Farrer.

I am convinced this was not the case – you’ll need to read Miss Willmott’s Ghosts for the full reasons why, but I am absolutely sure she had no romantic interest in Bowles (and I am equally sure he had no romantic interest in her).

Sir Frank had been very good to Ellen, flattering her by asking her advice, inviting her to events and giving her financial guidance. Besides, the plants that Farrer was insulting came from her garden. On top of that, by this point Sir Frank was, probably unwisely, lending Ellen money, and trying to find more loans for her from other people.

So – we are back to Chelsea.

Image (c) Berkeley Family and Spetchley Gardens Trust

To insult the garden at Friar Park was to insult the garden at Warley Place. Ellen stood outside the gates of the second-ever Chelsea Flower show with a large leather bookbinder’s satchel, handing out copies of Sir Frank’s tirade to anyone who would take them.

The Crispian Row did little for the reputations of any of the horticultural luminaries concerned. Gussy Bowles was mortified, Frank Crisp looked foolish and bombastic and Miss Willmott branded herself a shrew. The only figure who seemed to come out undented was Reginald Farrer himself, who quietly disappeared plant hunting abroad.

So why isn’t this incident better known?

Because exactly one month after this horticultural character assassination a real assassination took place: of the Archduke Ferdinand. After that, nothing would be the same again.

Image (c) Berkeley Family and Spetchley Gardens Trust

*Farrer continues the feud in his 1919 book The Rock Garden with an acidic, backhanded compliment. After describing Primula magaseifolia…

…as “a rather chilly and bitter tone of magenta-lilac (suggesting an acid old maid crossed in an unseasonable love affair)” he mischievously announces, “it was introduced by Miss Ellen Willmott in 1901”.