Ellen Willmott’s photographs range from whole plate (6 ½ x 8 ½ in) all the way down to absolutely tiny, and when they’re tiny they are weeny. That one of her on the front of the paperback version of Miss Willmott’s Ghosts? Not two and a half inches high.

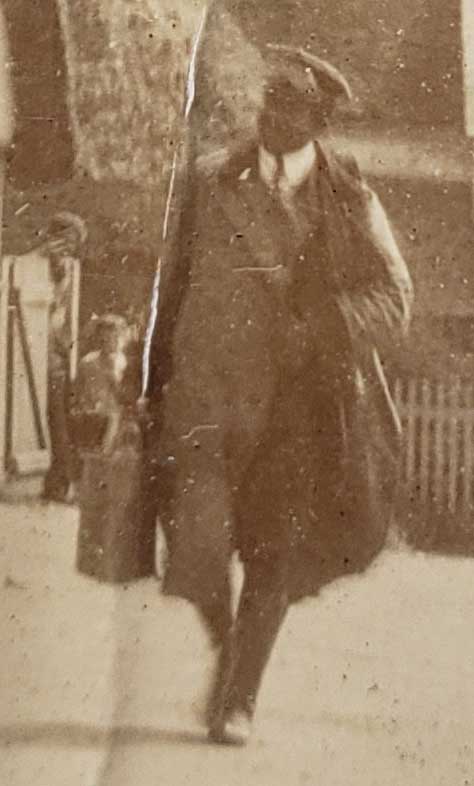

So when, without my specs on, I fetched up a Thumbelina-sized image of a smart chap in a uniform with knee boots, cap and a large bag over his shoulder, walking through Warley village, with the whole population out on their doorsteps to see him, I assumed he was a World War One soldier going to or coming back from the Front.

After all, Warley lost a lot of men in the war, we have the memorial to prove it.

It was only when I got home and was able to enlarge the image digitally that I realised who it was.

Ellen Willmott’s chauffeur, Monsieur E (we don’t know his first name) Frédéric, is a bit of a mystery. We know he came from Mozambique, and we know he was an educated, confident man, highly skilled in motor mechanics at a time when very few were. We also know that he was comfortable in his own skin and that he knew his worth. And that’s about it.

Audrey le Lievre, who was lucky enough to interview many elderly residents of Warley forty-odd years ago, tells us that when Miss Willmott returned from her Italian villa one summer afternoon in 1906 in a brand new, chain-driven Charron motor vehicle like this one…

…she caused something of a stir, especially when the village saw the driver. I am convinced she took this photo to commemorate the day, complete with gawking locals:

It’ s not just three people on the doorstep staring, don’t miss the two characters in the background, the child and the woman peeping over the fence.

They would have been used to seeing foreigners in the village. Ellen Willmott employed gardeners from many countries, not least her Swiss Alpine gardener, Jacob Maurer. M. Frédéric, however, is the only Willmott employee of colour that we know of – so far.

The reason I think this picture was taken on the day of M. Frédéric’s arrival is that I just don’t think so many people would have come out to gawp if they had seen him before.

He’s clearly in his uniform – we are just beginning to fetch up the dozens of bills and receipts for Ellen’s staff’s liveries…she spent as much on smart clobber for her gardeners, house staff, coachman and, here, her chauffeur, as she spent on everything else. He’s carrying his clothes in a kit-bag.

In his other hand he carries what looks like a car battery, though it can’t be as they weren’t introduced until 1918. I guess it might be a suitcase.

Rumours swirled. Some said Miss Willmott found him as a downtrodden rogue hanging around the docks at south of France, which saw arrivals from Africa every day. More romantic gossips whispered that he had once saved her life and she employed him out of gratitude.

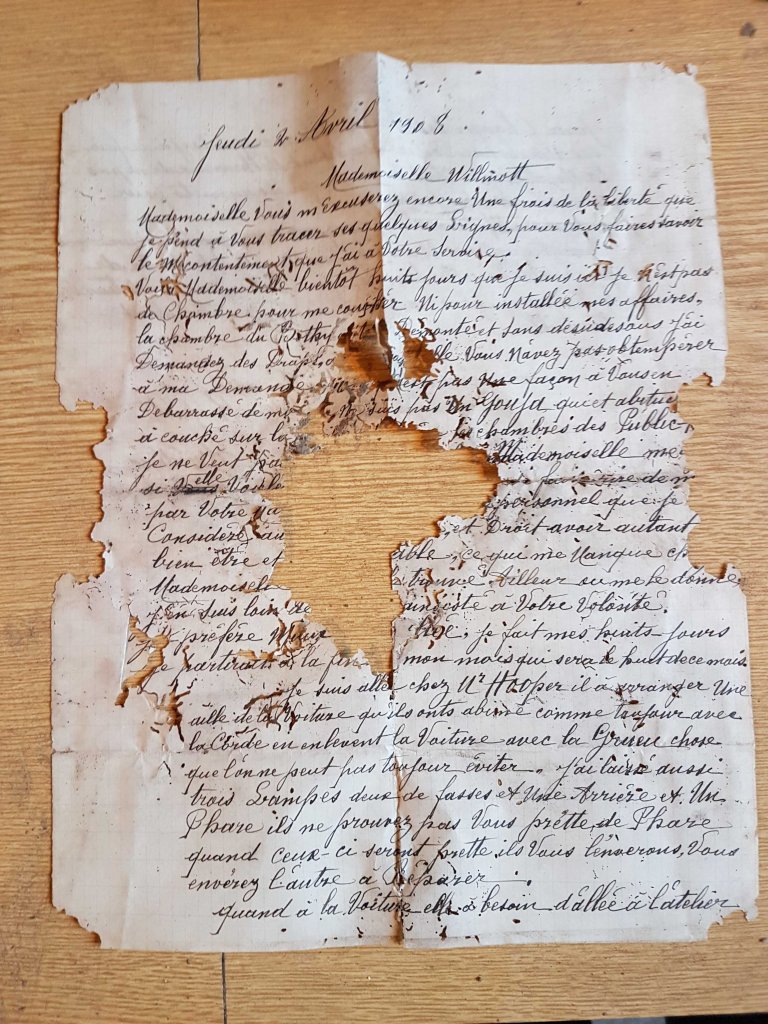

From the only letter we have ever found from M. Frédéric, we know his arrival was not a completely happy one. Alas, it has a giant hole in the middle:

…but we can tell many things, even from this fragment.

Firstly, just look at that handwriting. I have seen a LOT of handwriting from this period, all horrible scrawl or, if it is from servants, capitals or rounded lower-case, in laboured ‘schoolchild’ writing. This is neither of those. The hand is strong, readable and in excellent French. The manner is dignified.

Its scribe is clearly not some ne’er-do-well off the Marseille dock. He is both educated and skilled. He is also pretty upset.

This is not the first time he has written to her, we learn, in the eight days he has been at Warley. He still has nowhere fixed to sleep. The bothy is filthy and untidy; he is no gouja (bruiser) used to sleeping in such places.

It is usually said that M. Frédéric was accompanied by his (white) wife when he arrived, but the fact that he has been put in the bothy, a place for unmarried gardeners, makes me think she must have arrived later.

This, by the way, is the only reference I have ever found to Warley’s bothy (other than it was run by the Sayward family), and it’s not an attractive one. The unmarried gardeners’ quarters were next to the kitchen garden, some way down the road to the main pleasure grounds, more or less where the Headley Arms is now, though it was all Willmott land then.

M. Frédéric has, he tells Miss Willmott, had enough of these horrors. He has as much right to decent surroundings – and sheets! – as anyone else and he is unaccustomed to being laughed at. He will work out his month, then he will leave.

Such boldness from any servant in those days was rare, but M. Frédéric knows his worth. Chauffeurs – especially good ones – are in demand and what is left of the rest of his letter shows us why he is confident enough to speak he does.

He clicks into professional-mode. The car was damaged as it was winched from the ferry at Dover, and he is arranging for repairs. There will be further work needed, though, on the brakes and the headlamps. It will take around eight days so she should find a time when the car won’t be needed, and have it taken into Hoopers.

There is no ultimatum, no suggestion he is making empty threats. He is merely informing her he is unhappy and will be gone when his notice is served.

It clearly did the trick; indeed, Miss Willmott seemed to rather respect people who stood up to her, we have similar letters from Jacob Maurer, which resulted in similar capitulation.

M. Frédéric must have been given much better pay and/or conditions because he, along with Mme Frédéric, became respected pillars of the local community – he as chauffeur, she as a French teacher at the local school.

There are two more photographs of M. Frédéric, both utterly delightful and clearly taken one day when he had driven Miss Willmott to visit her sister Rose at Spetchley Park, then played with her children by the fountain in the gardens. It is clearly not long after he arrived, as the children are very young.

M. Frédéric drove Ellen all over Continental Europe, and gained quite a reputation for hurtling at breakneck speed, remembered with horror many years later by Rose’s husband Robert Valentine Berkeley. The Charron reached a dizzying 28mph if M. Frédéric put his elegantly booted foot down.

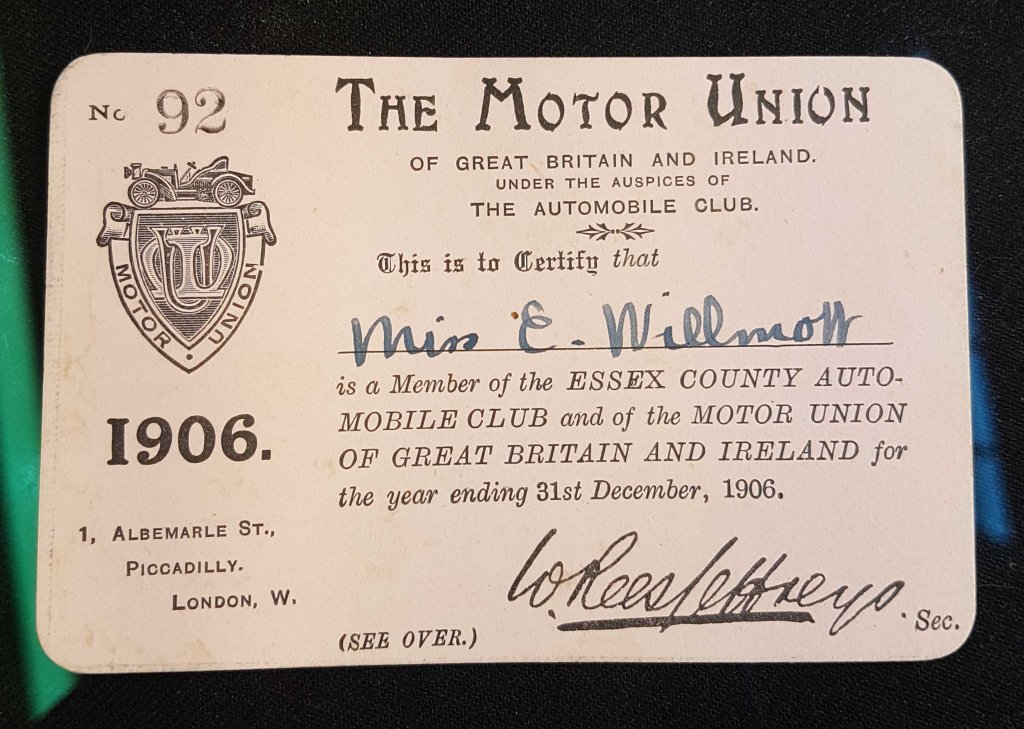

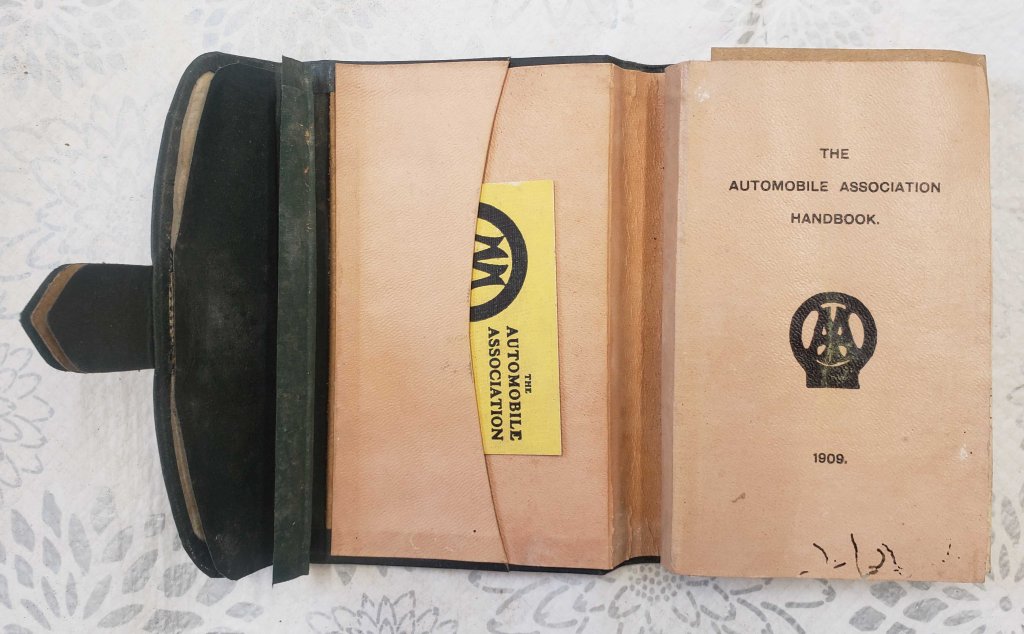

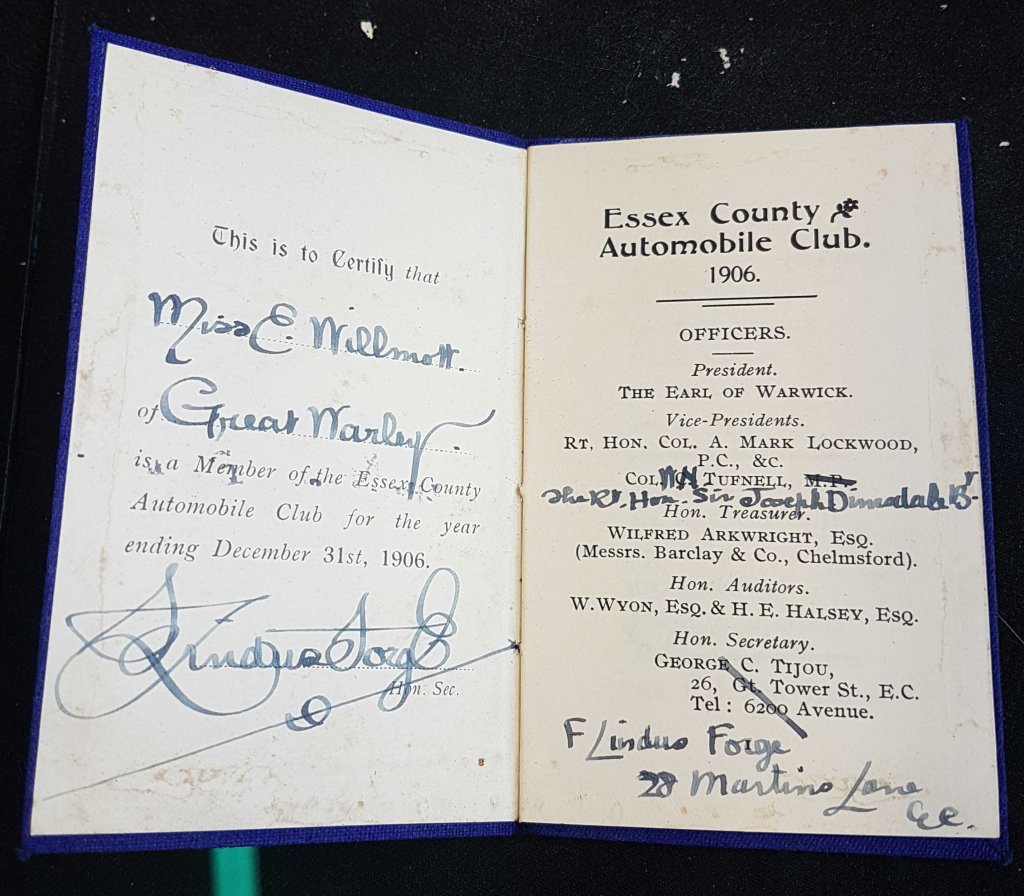

I have often wondered why Ellen didn’t drive herself – it’s just the sort of thing she would do, but I can’t see that she ever did, though she was a very early member of the Ladies’ Automobile Club (along with the regular AA, the RAC and pretty much every other breakdown club going, which probably says more about the reliability of motor vehicles then than any feminist solidarity).

I do wonder whether she enjoyed the attention she gained wherever she went – she and M. Frédéric became a well-known sight around London.

An article in the French garden magazine Lyon Horticole describes just what a sight Ellen and her chauffeur must have been. Its author, clearly dazzled by the sheer glamour of Ellen and her sister, describes being driven around the Ventimiglia countryside by Ellen’s ‘exotic’ driver. While he does mention the garden at Boccanegra, it is very much a by-the-by in comparison to the ride.

It makes for frankly uncomfortable reading today, and I don’t really know what to think of her if, indeed, Ellen did employ M. Frédéric for his looks rather than his mechanical and driving skills.

My gut tells me otherwise, though. She didn’t care a fig what people thought of her over other matters, she regularly employed foreigners when they had the skills she needed, and she corresponded with experts all over the world – if they had something interesting to say she was interested to hear it, whoever they might be or wherever they might come from. She needed a driver, M. Frédéric fitted the bill.

I’m going to give her the benefit of the doubt. She didn’t make a habit of photographing individual members of staff and certainly didn’t normally paste pictures of them into a photo album (with one glorious exception that I’ll write about another day…) but for M. Frédéric she bent her own rules.

This last photograph of M. Frédéric with Ellen’s nieces and nephew is still mounted, and still delightful:

I live in hope of finding more about him. Who knows what may turn up. There must be some relatives, out there, somewhere, surely…