SPOILER ALERT

Okay, if you haven’t read Miss Willmott’s Ghosts yet, avert your eyes – this post is Not For You. Nothing To See Here. Move Along Please.

For anyone else, however, who wondered what happened to the shy young German naval lieutenant who fell madly in love with Ellen Willmott then disappeared from her story at a rather disturbing moment, this is your lucky day…

…sort of.

Handsome, 25 year-old Johann fell head over heels for charismatic, 47 year-old Queen Bee Ellen while they were both taking the waters at Aix les Bains in 1905. You will already have read about how she ever-so-gently turned down his later, impassioned marriage proposal in Miss Willmott’s Ghosts, but Johann remained besotted and continued to write doe-eyed letters to her, sending her photos of himself on a horse…

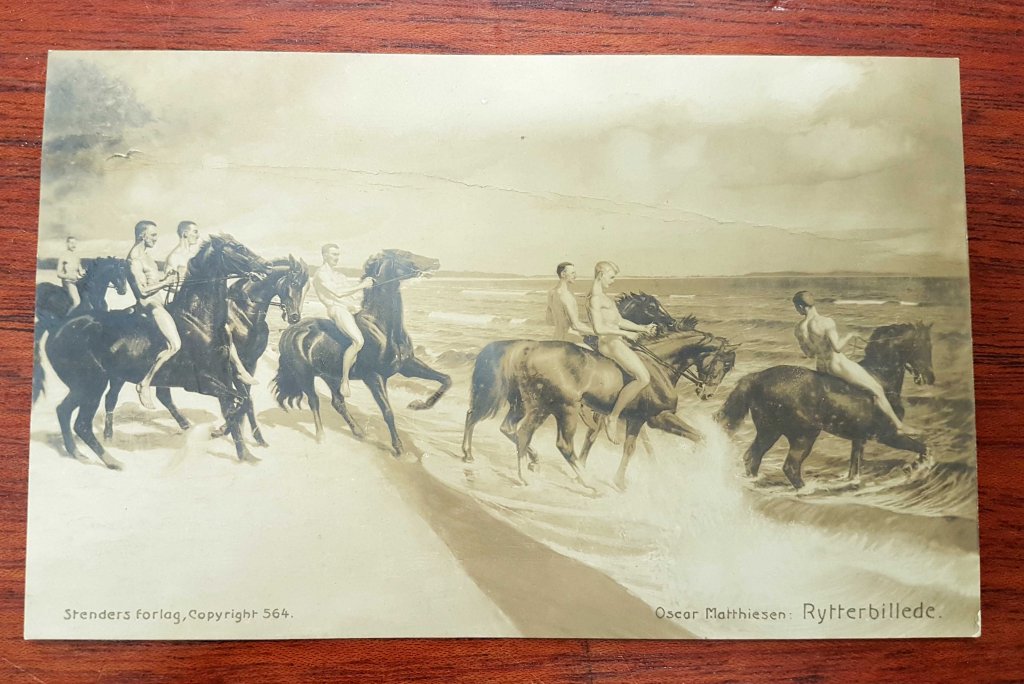

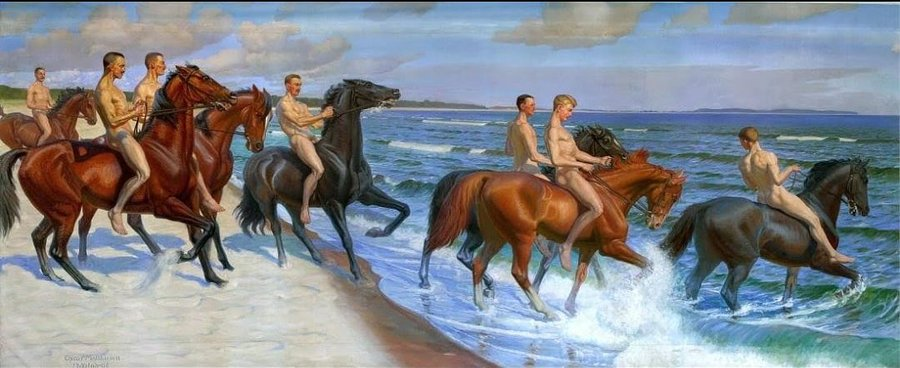

…a copy of his brother-in-law Oskar Matthiessen’s gigantic, frankly eye-popping painting of some naked soldiers watering their horses (let’s not even go there…)

…now in the Ystad Millitary Museum, Sweden and utterly enormous…

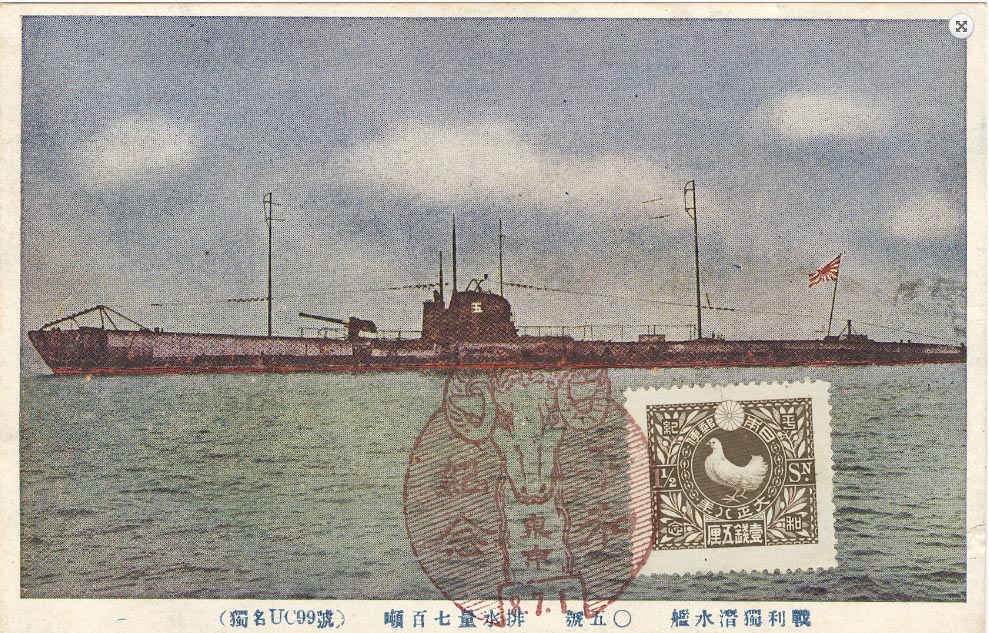

…and updates of the various, ever-increasing-in-kudos vessels he was commanding as he was promoted up the ranks, including the SMS Sleipner, dispatch vessel for the Kaiser’s yacht.

Johann continued to write to Ellen even after he met a ‘dear soul’, Elizabeth (his wife, not the sausage dog, whose name has not survived History).

…and sending Ellen snapshots of them both in their garden at Charlottenburg, Berlin:

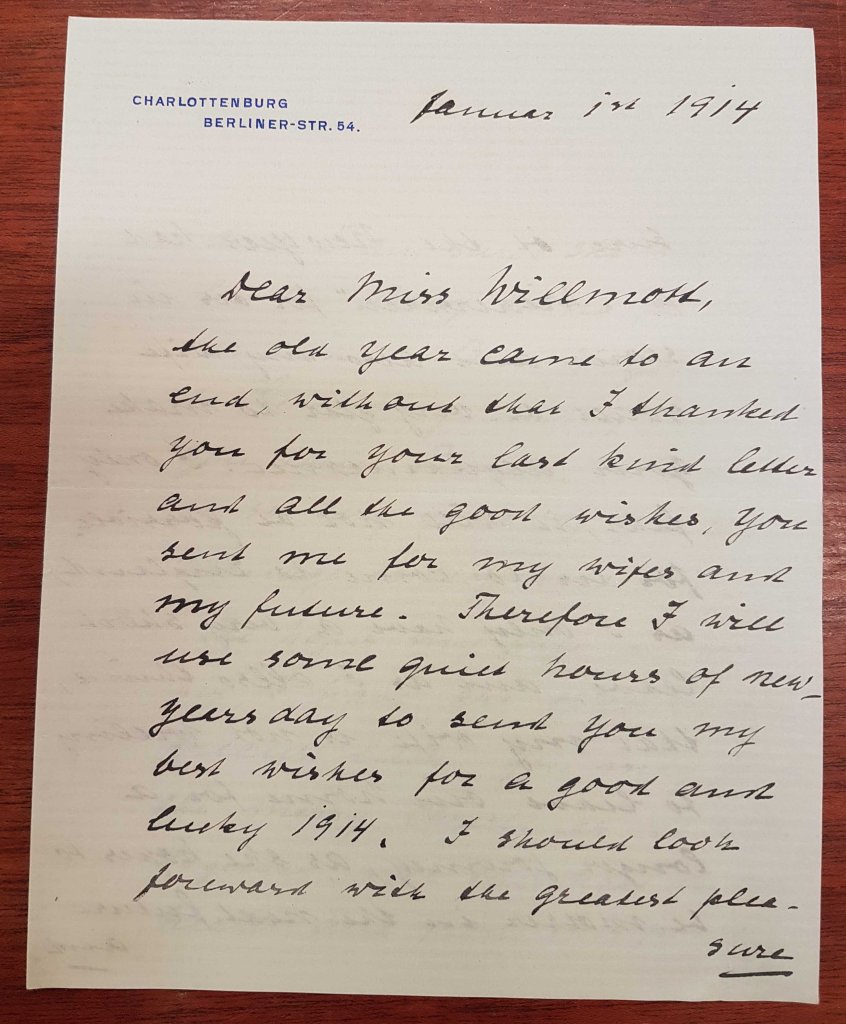

We last saw Johann Bernard Mann six months before World War One, on the wrong side of fate. His final letter is dated 1st January 1914, where he cheerfully hopes to meet Ellen when he comes to England that summer with the Kaiser’s retinue:

We all know what happened in the world to prevent that meeting and, after coming to the end of the little pile of letters with that cliffhanger, I couldn’t rest until I knew what happened next.

Buckle-up tightly, this is going to be a bumpy ride.

Mann was 34 at the outbreak of war. He had finally finished a dreary stint behind a desk and, delightedly, he told Ellen that his dearest wish – to return to active service – had been granted. No longer commanding the Sleipner, he’d been promoted and was now working as personal assistant to Imperial Navy-heavy, Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz:

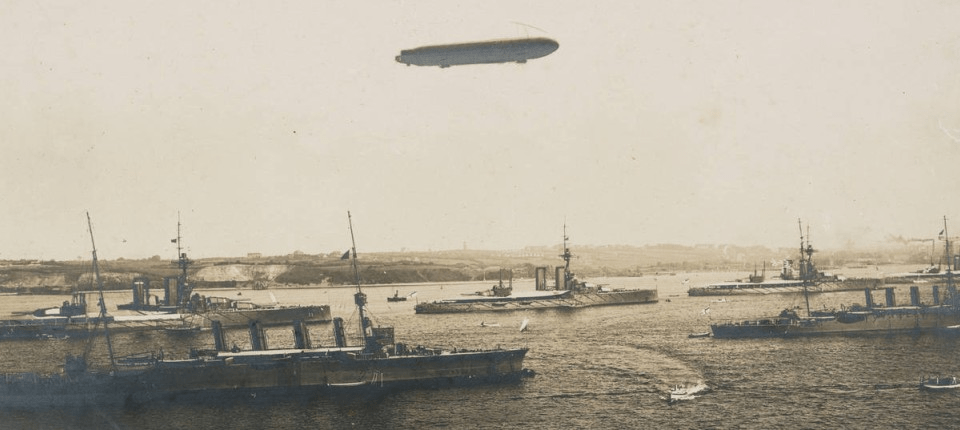

In June 1914, Mann was part of the German team welcoming four British battleships and three British cruisers at the annual Kiel Regatta.

On the 28th June, Kaiser Wilhelm, nominally Admiral of the British fleet, had just been ceremonially piped aboard HMS King George V and the two navies were happily yacht-racing, watched by a friendly zeppelin…

… when news arrived of some Unpleasantness In Sarajevo.

Although the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand was an apparent anarchist attack, European political relations had been strained for some time.

This was a delicate situation. German commanders urgently needed to confer about any retaliatory action before Russia waded in and the whole thing got out of control.

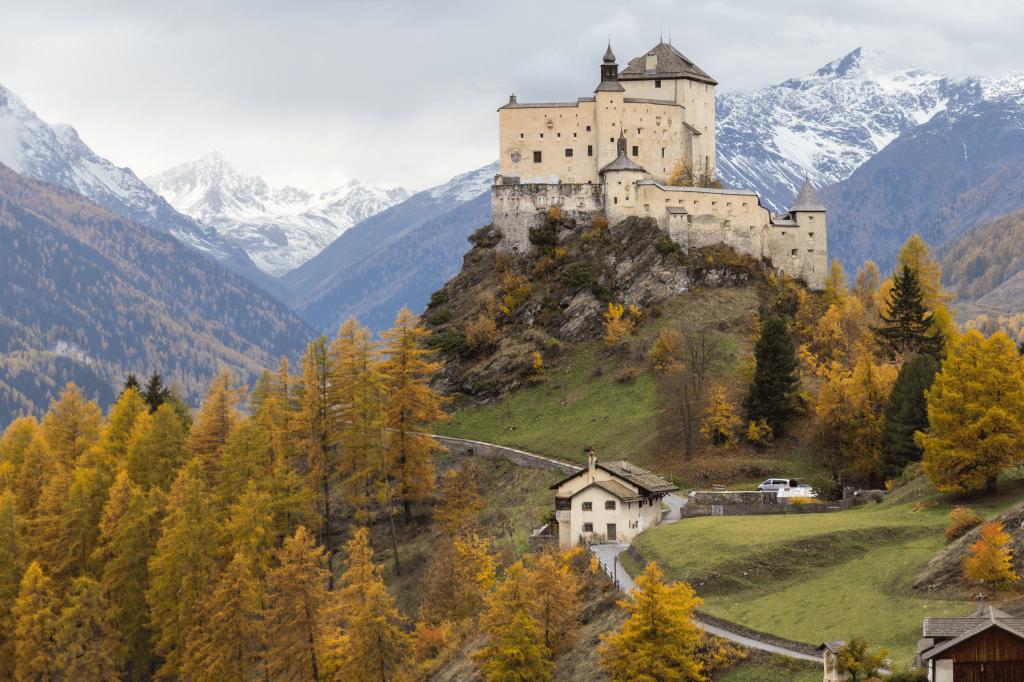

Unfortunately, at this critical moment, Admiral von Tirpitz was enjoying a spa holiday in the picturesque but inaccessible Tarasp Castle, Switzerland.

Tensions continued throughout July, as the world waited to see what Germany would do.

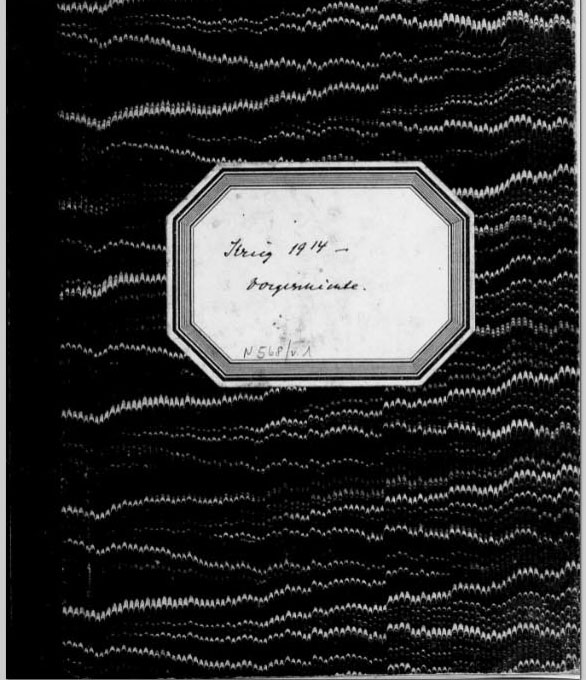

Most of what is known of the German side of the ‘July Crisis’ – and beyond, all the way to 1915 – comes down to three large, handwritten diaries kept by Johann Bernhard Mann in those fractious days.

Mann’s diaries, kept in the German Federal Archive, provide a first-hand account of how Germany managed to go to war with the rest of Europe. They deliberately include minute detail, so that his boss, fresh from the steam room, could hit the parade-ground running.

The diaries would later be plundered by von Tirpitz for his own memoirs but there is no dispute that these diaries are Mann’s work. Besides, I’d know that handwriting anywhere: it is the same neat script Mann had employed in his puppy-dog letters to Ellen nearly ten years earlier.

The journals were essential war-work – and are now important documents of world history – but Mann hated being deskbound again. He was desperate to fight.

In 1916, he got his wish. After a short time operating telegraphs on the SMS Konig Albert he became First Officer on the battleship SMS Prinzregent Luitpold. If he fought at Jutland, however, it would have been on another ship, as the Luitpold was in dry dock at the time.

By now it was clear there was no way he and Ellen Willmott would ever meet again. They were on different sides of history and those grim years would change them both.

The German Navy had a disastrous war and in November 1918 it faced ignominious defeat.

The Kiel Mutiny, on the 3rd November, saw regular German sailors in open insubordination at the humiliation they saw their commanders as having got them into, starting with the Prinzregent Luitpold.

Mann had moved ships and was now commanding the SMS Dresden but I am certain that, given the chance, he would have been part of that rebellion, and happily taken the consequences. Because by now Johann Bernhard was an angry Mann.

Most of the German fleet was commandeered by the British Royal Navy and corralled at Scarpa Flow. Along with the rest of the commanders, Johann Mann oversaw the scuttling (deliberate destruction) of his own ship.

The Treaty of Versailles brought fresh ignominy as Germany was forced to accept humiliation on humiliation. Ellen Willmott’s great garden-loving friend Max von Baden…

…a gentle man who had never wanted to be a politician – and even worked for the Red Cross during the war, helping POWs, rather than get involved with extremes – was forced to drink from the poisoned chalice no one else wanted: he was made Chancellor just as Germany was being trounced by the Allies in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles.

Ten years earlier, Johann had been keen to meet Max von Baden and was delighted when Ellen offered to introduce them. It’s probably a good thing it never happened as, after the war, the pair would Not Have Got On.

Max extricated himself from politics as quickly as he could, retired to his garden with his wife Marie Louise, and resumed writing to Ellen.

You can take a turn around his garden here:

Johann took a somewhat different path.

War had hardened him and like so many humiliated by defeat, he started to look for scapegoats.

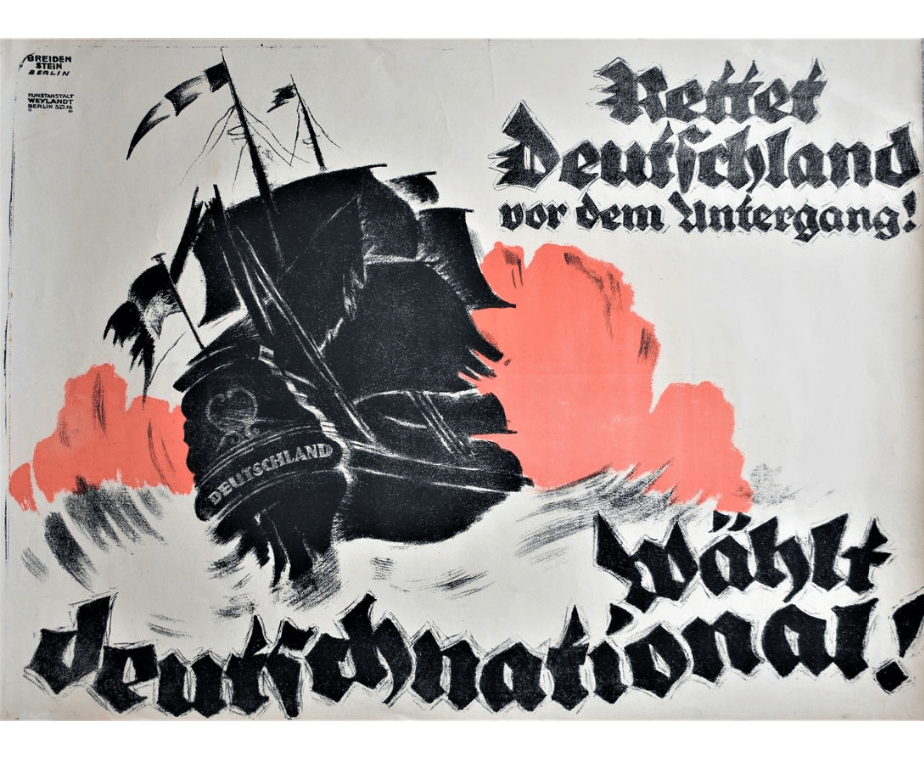

Discharged from the navy, he almost certainly became a member of the Deutschnationale Volkspartei (German National People’s Party), sprung from the short-lived Deutsche Vaterlandspartei, (German Fatherland Party) founded by his old commander, Admiral von Tirpitz.

From now on, sweet, shy Johann Bernhard Mann became a true believer in the resurrection of a new Germany.

In 1920 he began working secretly on the illegal construction of submarines for the German Navy in Japan. There is no proof he joined Adolf Hitler’s Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei but it is almost certain that he did, given his work in Japan and later work for the Cause.

Mann took a strategic advisory role with the German navy during WWII; it’s also possible he was involved in Japanese naval intelligence.

Things just got worse for him. His son (also Johann) died on the Western Front in 1940; Elizabeth died in 1943. Johann had nothing left to fight for but his patriotism.

The Red Army was on the march to Berlin. Mann joined the Volkssturm, the German equivalent of the British Home Guard, and prepared to fight one last time: defending his city.

On 27 April 1945, Johann Bernhard Mann was badly wounded during the Battle of Berlin. He died in Spandau hospital 19th May, 1945, eleven days after VE Day.

What can we make of all this? I really don’t know. There’s little value in pondering ‘what-if’ – for so many reasons there was never any chance Ellen Willmott would actually marry her handsome lieutenant.

Mann had had a difficult childhood, of shockingly-for-the-times divorced parents with financial problems, and lacking a father figure. With that marvellous tool hindsight it’s possible to drag ‘signs’ out of his letters but it always will be just that: hindsight.

His letters – always formal, always polite, reveal a lost soul who would later live in times of huge change and national humiliation and while that wouldn’t automatically turn someone into a Nazi Johann’s experiences in and after WWI on top of that just might have tipped him over the brink.

Perhaps all he can do today is stand as a lesson as to how ostensibly decent people can find themselves whipped into mass hysteria, especially at this most worrying time. What is history, if not to learn from our mistakes?

By the way, the internet will tell you that, in 1908, Mann founded a charity in his own name to support young people’s Protestant education. This is not true. An existing fund changed its name to the Johann Bernhard Mann Foundation after his death when, with no surviving relatives, he willed his considerable estate to the charity.

Very interesting! Thank you!

LikeLike