There is an intriguing legend that while on holiday in the Alps, a 19 year-old Ellen Willmott bought, on the spot, a Swiss shepherd’s hut from St Bernard Pass / Bourg St Pierre because someone told her Napoleon Bonaparte stayed in it one night during his famous Alp-crossing exercise.

The story continues that she had it shipped back to England where, in the days before an entire alpine ravine at Warley was even a twinkle in her eye, Ellen had it erected by the lake.

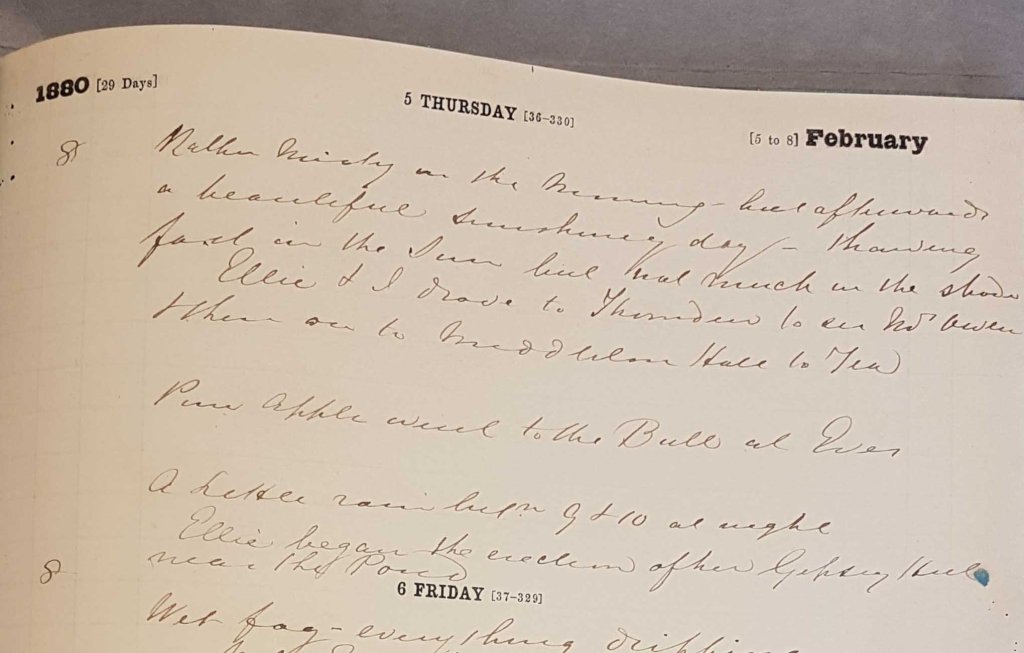

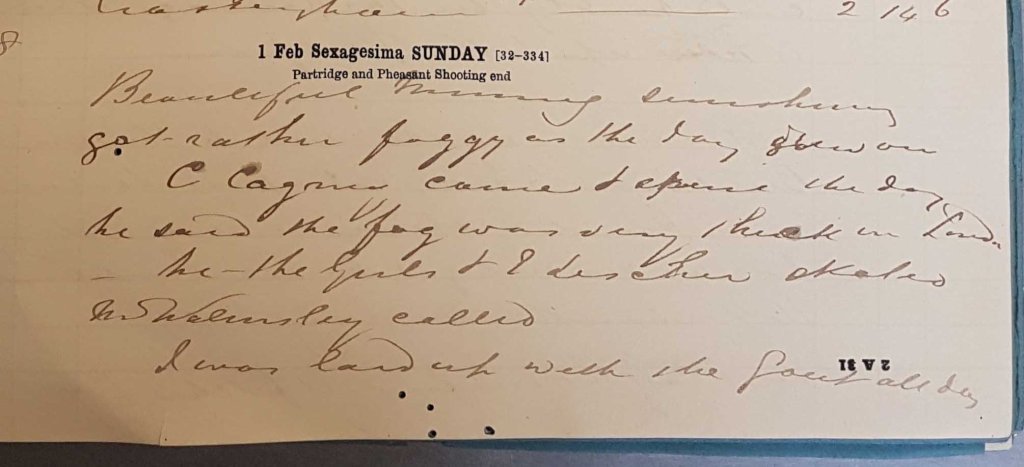

It’s not entirely impossible. Fred Willmott’s diary, February 1880, tells us:

“Ellie began the erection of her Gipsy Hut near the Pond”

I feel sorry for the construction team; just four days earlier the same pond had been so frozen she was skating on it:

Thing is: was this ‘Gipsy hut’ the same thing as ‘Napoleon’s cabin?’

So – today’s post is the second in an occasional series about Ellen’s (many) summer houses. Strap-in, this is going to get nerdy…

For years I wasn’t totally convinced what Fred meant by the ‘Gipsy hut’. Ellen eventually had at least eight summerhouses at Warley but it all gets very confusing around the lake, especially when other documents talk about there being a boat house there too.

Audrey le Lievre tells us Ellen had Boney’s hut filled with herdsmen’s gear for dressing-up (Ellen loved fancy dress, but that’s for another day…) and had a landing stage built to serve it.

The archaeology in much of Warley is weird. It’s often difficult to marry photos and even maps with what’s there on the ground. It’s especially strange around the boating lake. Not only are there no signs of a Gipsy hut in any archaeology so far, there is no sign of a boat house either.

Basically, all we’re left with today is a corner of the dried-out lake, fitted with an iron bar and mooring ring. There is no obvious place for a landing stage and certainly no room for a boat house.

Thanks to modern boundaries, the way the path now works makes it look as though, in order to fit into the plans, the lake needed to have extended way out into the meadow (now fenced-off). It didn’t, though it was in two parts with an extra added island, which is very confusing.

However, we now know that a Swiss chalet, Napoleon’s or otherwise, absolutely did exist, even up to 1920.

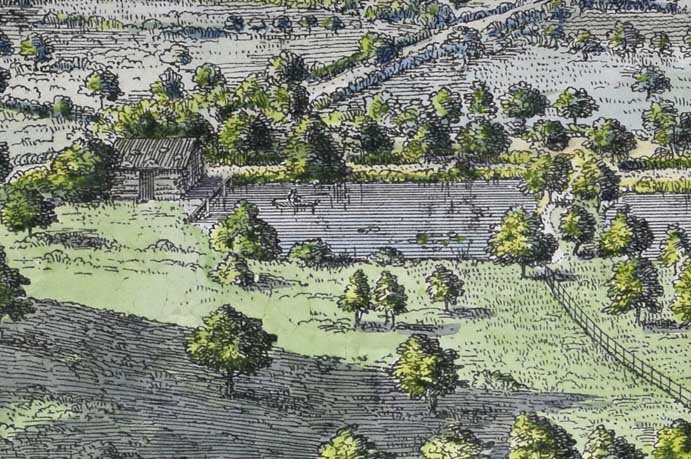

The first clue is in Ellen’s famous ‘Kip and Knyff’ topographical drawing. The cabin is deep in the distance, almost on the horizon.

It’s just about visible in the regular black and white image (btw, Warley Place volunteers sell excellent prints of this on Spring Open Days, well worth the paltry sum charged, £3 if memory serves), but it’s much clearer in Ellen’s coloured version, which we found in 2019:

This clearly shows the landing stage – but no boat house.

I wasn’t the only one who doubted the very existence of a boathouse – in the 90s much-missed Warley research veteran Ray Cobbett wrote

“As to the boat house, I’m beginning to wonder if there ever was one.”

Let’s park that one for a minute; we’ll come back to it, promise.

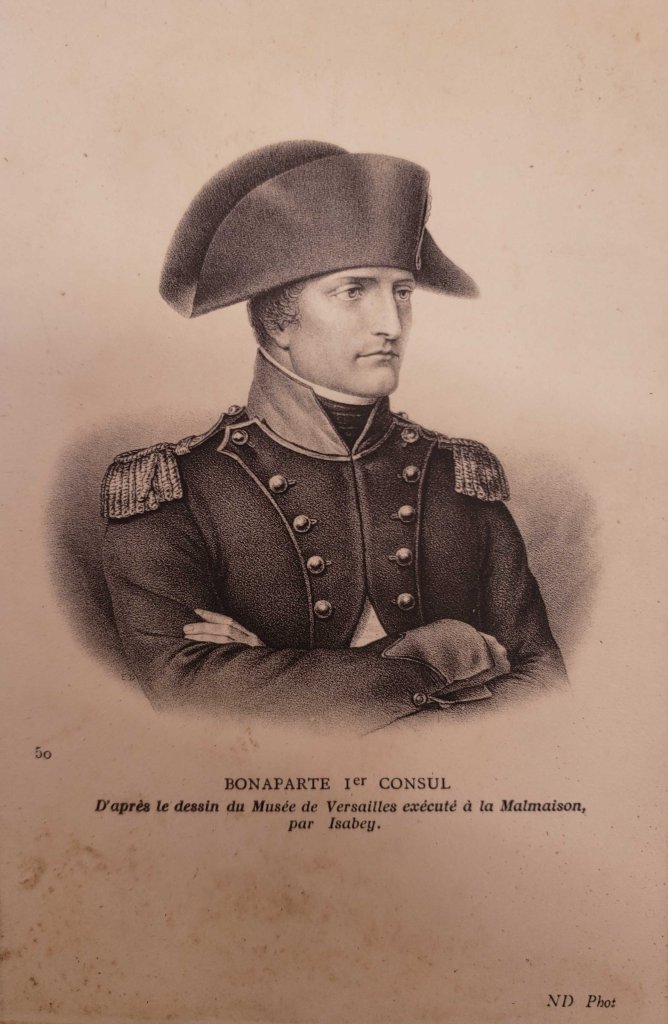

Because Ellen didn’t just allegedly buy a Swiss chalet because someone randomly famous once slept in it.

She was crazy for Napoleon, a character trait that has often been used against her, implying she was some jumped-up, little dictator.

Heaven forbid she might have admired something else in him – perhaps his battle tactics, the romance of the period, the man’s charisma – or his ability to ‘work his way up’ through unfriendly ranks.

Ellen may have been born with a silver spoon, if not in her mouth, certainly at chomping-distance, but as a woman she seems to have suffered from Imposter Syndrome, not least due to her inferior ‘girl’s’ education. This was not unlike the little man himself, who also received an imperfect – and interrupted – schooling, albeit for different reasons. He did alright for himself, why not Ellen?

Plenty still admire his British counterpart Nelson; perhaps people have thought her unpatriotic to go hell-for-leather for a Frenchman.

Non-Willmott-fan William Stearn had a different take on the Boney-problem: that Ellen’s alleged bitterness came from spending her life waiting for a man like him:

“Probably only a strong-willed, distinguished, intellectually eminent and rich man could have found favour with her but she never met her Napoleon”

Frankly I neither know nor really care why she was so keen on him but keen she was.

Last November, during a regular mouldlarking dip into the Bankers’ Boxes of Doom, I rocked up Ellen’s catalogue of Napoleon-related books:

…containing pages and pages of numbered volumes, along with their position in her Napoleonic library:

Ellen didn’t just collect readables, however, she wanted the lot.

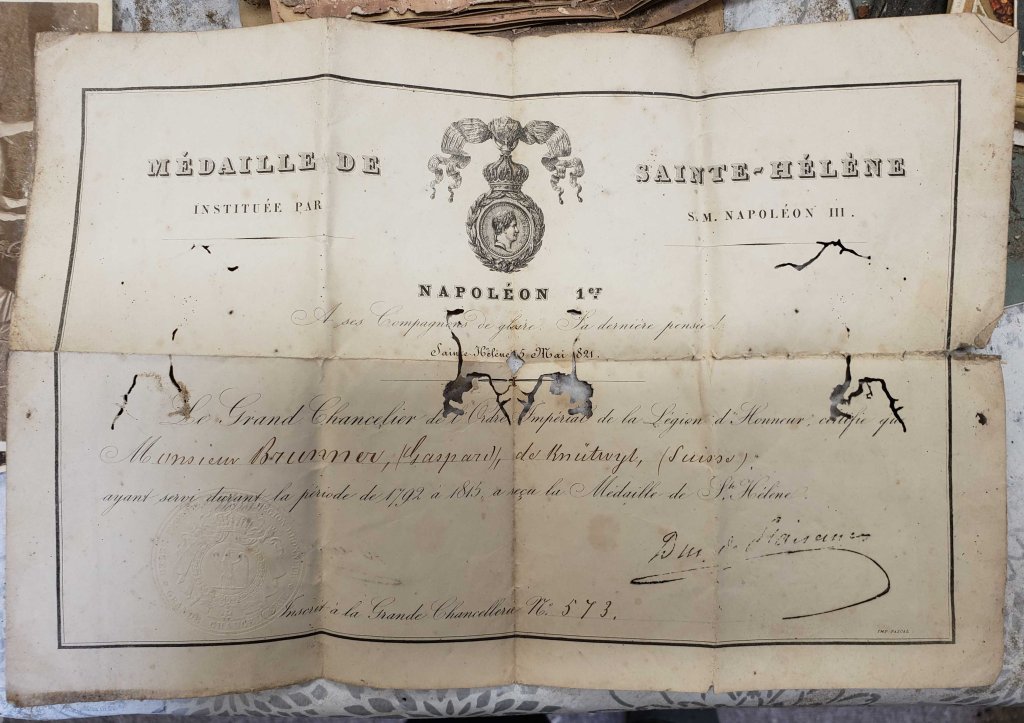

She had objects, miniatures, paintings, busts, commemorative medals – and original certificates, some of which escaped the auctions and we’re finding now:

Ellen also had one, perhaps two first edition copies of Pierre-Joseph Redoute’s famous illustrated album Les Roses, created for Napoleon’s consort Josephine:

…and, of course, at least two but probably far more of the original watercolours produced for the book. I am convinced that she based her own magnum opus, Genus Rosa, on that volume.

Last July I pulled out what has to be well over 100 postcards from Ellen’s personal pilgrimage to Malmaison, the Empress Josephine’s country retreat – where she began the world’s first rose garden – here are just some of them:

The visit to Malmaison’s rose garden should have given her pause for thought. It was, by Ellen’s day, a ruin:

I am sure it wouldn’t have crossed Ellen’s mind that her own home might suffer the same fate but nevertheless, from the relative number of postcard copies, she clearly preferred to think of it as it once was:

I am not yet familiar enough with Malmaison to recognise it in Ellen’s photographs but I’m hopeful she will have taken some; of course it depends on when she went, it may have been so early that she hadn’t yet taken up photography. She certainly bought a lot of postcards for someone who’d lugged a camera along.

Obviously we only have the unwritten cards, but each of them has multiple copies. The ones she bought most prints of are the romantic, ‘what used to be’ images…

…there are fewer ‘what’s left now’ pictures, but it’s clear she bought several copies of every view available in the gift shop, including interiors:

Her visit could have been any time between 1880 and 1900; my money’s on earlier as I just don’t think she could have waited to visit such a (literal) shrine.

Horticulturally, Ellen was confident enough in her vision not to copy Malmaison’s classical styling; however much she may have admired it, it just didn’t suit her own, wild-garden ideologies…

…but I do wonder if she found inspiration from some of the ‘wilder’ areas in the garden as presented to her in the late 19th century. Take this photo of a woodland pool at Malmaison:

…then look at what’s left of Warley’s lake:

…which brings me back to Ellen’s Napoleonic Chalet, and that missing boat house…

Things only began to really fall into place when the photos started to turn up.

Slowly at first, when we found a print made by Ellen, depicting the lake with the cabin, but made on heavily textured, fake-canvas paper, which meant we couldn’t zoom in on it.

Things improved slightly when we found an Alfred Parsons painting from exactly the same angle.

Then another Parsons, that could only have been painted from the mysterious landing stage:

Then a photo, from the same position, which John Cannell and I took to the corner of the lake where the iron bars remained, to try and work out the angle. It’s really hard to get your bearings these days as the woodland has grown up and the direction of the modern path creates a strange optical illusion.

It’s worth remembering that by the time the volunteers arrived in the 1980s all the original paths were lost under jungle, so they made their own. Only now are the team beginning to rediscover Ellen’s routes around the garden.

It did look about right, but that landing stage was an issue.

It took another couple of photos, of people on the landing stage, to work out the problem – and solve the issue of why there are no foundations and no boat house.

Basically Napoleon’s cabin WAS the boat house, which we finally proved with this shot, which clearly shows a boat moored underneath the chalet:

The hut/ landing stage projected out over the moorings, creating, in effect, a little boathouse under the cabin.

We couldn’t find foundations because a) the bit on land had never had a permanent base and b) half of the hut and landing stage were built onto stilts in the lake.

Here is a side view:

Admittedly it’s not one of Ellen’s best, but it DOES (probably accidentally) show the hut as seen from another now-disappeared summer house, just below the Spanish chestnuts. Here it is in grainy closeup:

We have just rocked up a couple more images, firstly of the lake side…

…which has some strange writing carved into it.

Quite a few of the curious pieces of furniture Ellen brought back from Switzerland, Germany and eastern France have odd legends carved into them and I confess I don’t know what any of them means, but I think it’s folk-art rather than Ellen’s own additions. If you’d like to have a go at translating it here’s a closeup:

Let me know what you make of it.

We also found a view of the non-lakeside entrance…

…complete with a little wooden icon…

but that’s about it for images. The ivy on the sides and the fact that Ellen didn’t photograph the hell out of her very, very expensive purchase (I’d love to find that shipping receipt…) suggests to me that she started her serious photographic career some time after the novelty of Napoleon’s hut had begun to wear off in favour of new enthusiasms.

She never lost her enthusiasm for the emperor himself.

The hut was still in (probably rotten) existence in 1920, at a time when Ellen was in such dire straits she thought she was going to have to sell and Warley was slated for auction. The catalogue doesn’t go into detail; the feature is described only as a ‘Swiss Chalet with landing stage’ which is where I assume Audrey found the description:

By the 1935 auction, when Warley was actually sold, it seems that even if a few sticks remained, the chalet wasn’t in any kind of state to attract attention and the catalogue doesn’t mention it.

Whether the man himself ever slept in Ellen’s garden shed – well, who knows. I sometimes wonder how many ‘huts that Napoleon slept in’ were sold to gullible tourists in the mid 19th century and may still grace country gardens around Europe.

Perhaps I’m just being uncharacteristically cynical. After all, he had to sleep somewhere…