The most obvious reason why we remember Ellen Willmott as a horticulturist is because, however fragmented, there is at least some evidence of her horticulture.

In her lifetime, however, Ellen was known equally – and in some circles more – for her musical abilities. Some obituaries actually describe her as ‘musician and gardener’ in that order.

Ellen was one of those sickening people that could get a tune out of anything and from an early age she collected musical instruments of the world. Her father had Warley Place’s billiard room turned into a music room for her, dominated by a gigantic, gas-powered organ, and in 1906 she had the room enlarged, including a gilded, domed ceiling for the acoustics.

Ellen was crazy for music; mainly classical but she also became involved in the folk song craze headed up by Cecil Sharpe, was heavily into early music and wasn’t averse to the odd comic music hall song, either.

She collected regular sheet music by the sheafload but also original manuscripts and signed ‘autograph scores’ by famous composers of history. Most of these got sold in 1935 but the odd one rises to the top of the mould-soup from time to time – here’s Ah! Non Fia Sempre Odiata from Il Pirata, personally autographed by Vincenzo Bellini:

You can have a little listen here:

So there was no way Ellen was going to turn down the opportunity of getting to know one of Britain’s greatest-ever composers…

Sir Edward Elgar is an-almost exact contemporary of Ellen’s. He was born in 1857, one year before her, and died in 1934, the same year as her. Like her, he was brought up a Catholic, unlike her, that was not a done deal. And here’s a thing:

The late 19th century saw a phenomenon that’s all but forgotten today: the Catholic convert. There were loads of them – so many that newspapers used to run stories listing all the recent celebrity converts:

Edward Elgar’s mother was one such convert and brought up her son as a devout Catholic, much to the disapproval of his father. Young Edward went to school just outside the grounds of Spetchley Park; albeit long before Ellen or her sister Rose even knew the place existed.

In 1955 music critic Ernest Newman* wrote in Edward Elgar and his World “Elgar told me that as a boy he used to gaze from the school windows in rapt wonder at the great trees in the park, swaying in the wind”.

Elgar was specifically referring to a grove of rather majestic Corsican pine trees, of which I have just realised I only have one, absolutely bloomin’ awful photo:

Elgar had grown up in a relatively humble situation but as he became better known, he was introduced to a much wider circle of people, including the (also-Catholic) Berkeleys of Spetchley, into which, of course, Ellen’s sister Rose had married in 1891.

A regular visitor to Spetchley, Elgar once signed the visitor’s book with a line from The Dream of Gerontius:

Possibly his most profoundly Catholic work, this choral masterpiece had been composed in 1900, based on a poem of the same name by John Henry (later Cardinal) Newman, another Catholic convert. It relates the death of a pious old man, his soul’s journey to judgement before God and, crucially, its passage on from there to Purgatory.

In the extract above, Gerontius’s soul has just passed through the gates into the House of Judgement where he hears surging, heavenly music reminding him of

The summer wind among the lofty pines

Ever since, those Corsican pines at Spetchley have been considered the composer’s ‘lofty pines’. You can still see them today. It is best whispered that Spetchley’s Head Gardener Chris Miller counted the rings of a felled specimen and in 1869 these magnificent specimens would have been ‘lofty’ only to a very short schoolboy very close up indeed…

We know a little about that visit through Ernest Newman. He tells us that poor old Elgar had undergone an unpleasant electric cautery on his throat just a few days before he arrived, which he bore “splendidly” and, somewhat randomly, mentions that a chaplain who was also present wore full Dominican robes at dinner. How does Newman know this? Er, he was there – see his signature above those of Sir Edward and Lady Alice:

…and above him, another signature you may recognise, though I am less comfortable about the date on that.

Annoyingly, Ellen does not very often sign Spetchley’s visitor’s book – she was in and out of her sister’s house all the time and it is entirely possible she couldn’t be bothered to sign the guestbook twice in the same week.

We can be sure she was present at the same time as the Elgars at another house party, in 1920, though:

This will have been a rather sad occasion as here, Sir Edward’s plus one is his daughter Carice; his wife had died of lung cancer in April that year. At least they will have been assured of a sympathetic welcome at Spetchley.

One thing I am certain of: there is no way Ellen, a consummate musician, would have missed any opportunity to hobnob with the most famous composer of Edwardian England, almost certainly playing music with him at Spetchley. After all, one of the most popular evening entertainments at house parties was inveigling guests – especially famous ones – to play or sing.

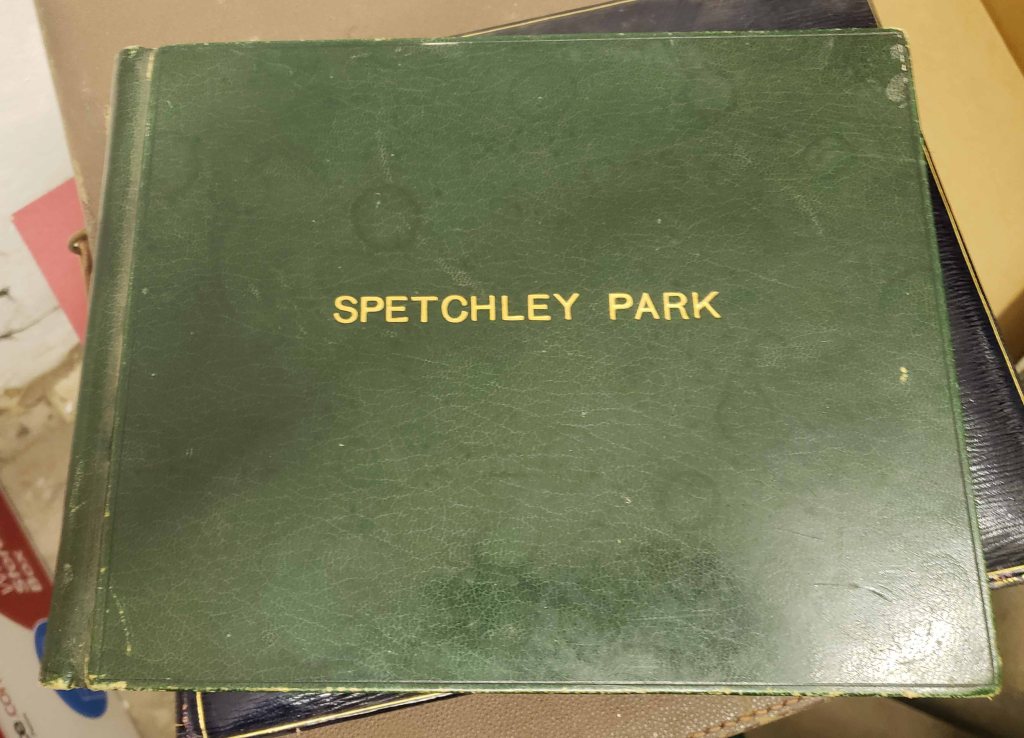

Just how early they met, however, is up for speculation. The only Spetchley Livre d’Or that currently survives begins in 1915 so although we have Edward Elgar and his wife Alice appearing several times we have no idea of how long – or often – the composer had been a houseguest before that.

We just have to hope that either the other, earlier visitors’ books turn up, or that someone mentions Sir E in letters that haven’t been read yet (believe me, there’s a few of those to go…)

We do have images though, of one such house party – probably the 1916 kneesup – where Edward has decided to go fishing.

A whole series of snapshots show him getting his gear together…

…rowing out on the Spetchley lake…

…and proudly laying-out his numerous catches. Sorry about this atrocious photograph – I was trying to snap all of these in very low light…

And here’s another thing we can’t be sure of: the snapper. Was it Ellen – or her niece Eleanor, who was also becoming interested in photography by this point? We can’t know for sure, but there are clues. Firstly, Ellen is not in any of the shots – this could of course mean she wasn’t there, but equally that, as usual, she was behind the camera.

Here is another clue:

This is Elgar apparently doing some kind of dance, with the Berkeley children in the foreground. The older girl has her back to us but I’ll lay money on its being Eleanor. It looks as though she is taking a photograph (the camera bag is over her shoulder) which means that Somebody Else is taking this set of pictures. No one else at Spetchley, that I know of, other than Ellen, was into photography at that time.

Who knows? Let’s face it, these are not great shots by anyone’s calculations, even if I had been photographing them in good light. There’s no competition for artistic supremacy here. They are interesting only for their subject matter: a capering National Treasure. Ellen – if it is her – is snapping, not photographing. She’s capturing fleeting moments with people whose company she values.

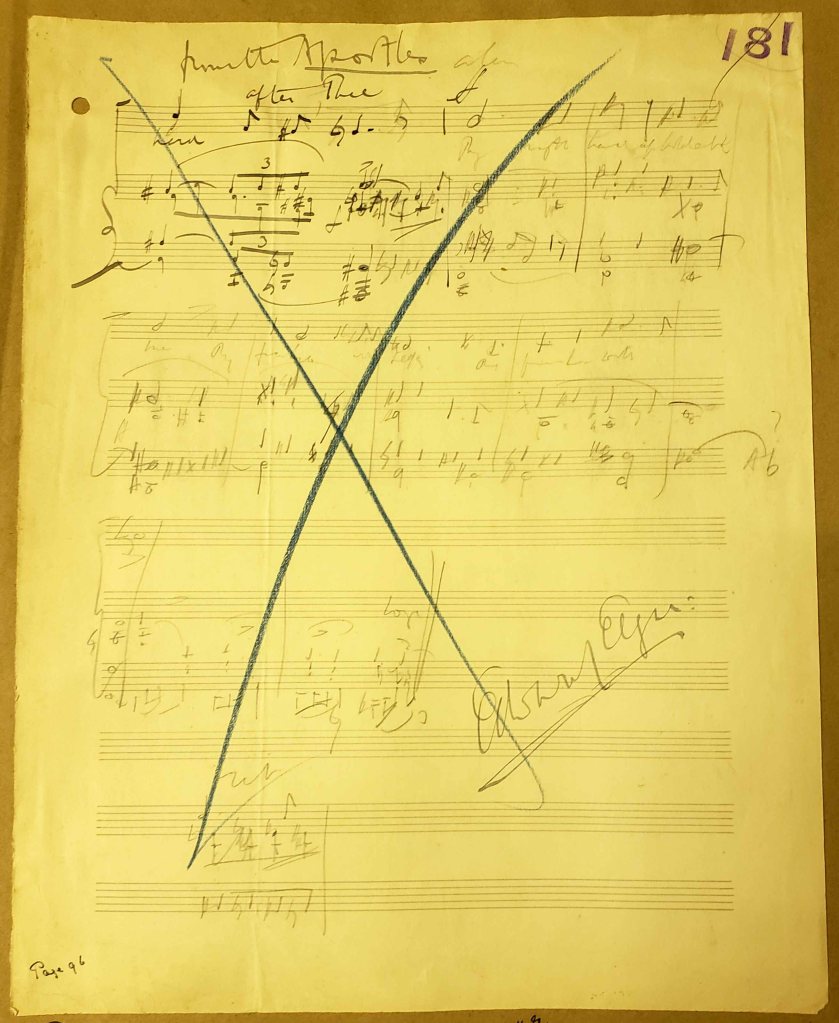

Certainly she was not the only person who was a little starstruck. We found a scrapbook – not Ellen’s; from the handwriting, I think it was kept by her brother-in-law, Robert Valentine Berkeley. In it, he has pasted a piece of manuscript clearly fished out of Elgar’s waste-paper bin, as it’s been crossed through, but then signed by the man himself.

By it is written:

Page of the original score of ‘The Apostles’ given to me by Sir Edward Elgar at Craiglea** Malvern where he composed it. The inspiration came to him from the picture of Our Lord on the mountain, the photo of which Lady Elgar gave me

Here is said picture (sorry about the image – again, light levels were not on my side…)

And below that is a signed photo:

..So RVB is a fan, too.

I will lay money that Ellen had her own scrapbook. As a ‘modern’ composer, however, any Elgar works in her vast collection of sheet music will have not been listed in the auction catalogues of 1934. His manuscripts would not have been considered ‘old’ or ‘special’ enough to turn up in the Sotheby’s sale and he will just have been lumped in with the scores of Lots merely labelled ‘orchestral music’, ‘choral works’, ‘instrumental’ or just ‘ditto’ in the main house auction. So we can’t tell for certain that she owned and played his works. But she was a member of the Bach Choir for over twenty years. She must have sung at least some of his works. I see they’re even performing Gerontius next Tuesday in Kings College Chapel.

This score is from much later – the Three Choirs Festival, 1965, and in the Spetchley collection:

…and I am told there is a box marked ‘music scores’ at Spetchley, which I guess we’ll get round to at some point.

What does turn up in Ellen’s stuff on a regular basis, is Elgar memorabilia, including an entire set of souvenir postcards of the man himself, each celebrating a different achievement. Here’s Gerontius:

There is more to be found about Ellen’s relationship with Edward Elgar. What it is, I don’t yet know. I’m betting they will have performed together on numerous occasions – even if only in one of Spetchleys’ grander salons. Watch this space.

In the meanwhile I leave you with another picture of Sir Edward fishing at Spetchley, watched by either his wife Alice or Ellen’s sister Rose. Frankly, like so much in the Berkeley archives, at this distance – both in time and photographically – it’s hard to tell…

*No relation, by the way, to Cardinal Newman – the music critic was actually born William Roberts and changed his name to Ernest Newman when he, too, converted to Catholicism, implying an ‘earnest new man’.

** Actually Craeg Lea